|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 28(6); 2013 > Article |

|

To the Editor,

Penicillin is the first b-lactam antibiotic and a member of the most widely used group of antibiotics. It has effects against many kinds of microorganisms. Although many types of bacteria are now resistant, penicillin is still one of the most useful antibiotics. Many kinds of adverse reactions to penicillin, such as interstitial nephritis, are well known; however, hemorrhagic cystitis is a very rare and obscure complication. To the best of our knowledge, there are only three previous reports of penicillin G-induced hemorrhagic cystitis in the English-language literature. We report herein a case of penicillin G-induced hemorrhagic cystitis and present a review of the literature.

A 63-year-old woman was hospitalized because of a 2-day fever and right hip pain. She had undergone total right hip replacement arthroplasty 10 years previously. About 6 months previously, the artificial joint had been removed because of a prosthesis-related infection. At that time, she had received cefazolin and cefuroxime for each week. After Streptococcus dysgalactiae had been identified by polymerase chain reaction from infected tissue, penicillin (500 million units every 6 hours) and gentamicin were administered for 9 days. Because of peripheral phlebitis, the penicillin and gentamicin were changed to ceftriaxone. The patient recovered and was discharged after 1 week of ceftriaxone administration.

The patient subsequently developed redness and mild tenderness on her right buttock and thigh. Laboratory findings revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell [WBC], 12,900/mm3) with a left shift and C-reactive protein (CRP) elevation. Hip magnetic resonance imaging revealed fluid collection around the previous operation site on the right hip and an enhancement in the bone marrow of the femur and soft tissues. These findings suggested septic arthritis and adjacent osteomyelitis. The patient underwent surgical drainage of the abscess of the hip joint and was empirically treated with vancomycin for 6 days. After penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus agalactiae had been isolated from the pus and tissue culture, vancomycin was changed to penicillin G. The administration of penicillin G (400 million units every 4 hours) was planned for 5 weeks. Her fever and CRP level declined soon after treatment was initiated.

Frequent urination and dysuria developed suddenly on the 24th day of penicillin G use. Urinalysis showed mild pyuria (WBC, 10 to 19/high power field [HPF]) without bacteriuria or hematuria. The pyuria was considered to represent the development of the acute cystitis. Cefpodoxime was added, but her symptoms did not improve. Hematuria (red blood cell, > 100/HPF) developed and the pyuria (WBC, 30 to 49/HPF) increased in severity, and gross hematuria appeared after 7 days. Repeated urine cultures were negative. Cefpodoxime was changed to ciprofloxacin 6 days later, but there was no improvement, and the patient suffered continuously from frequency and dysuria. There was no fever, leukocytosis, or renal insufficiency. However, the CRP level increased slightly from 1.53 to 3.57 mg/dL, and the percentage of eosinophils in the peripheral blood increased dramatically from 0.5% to 18% on the 35th day of penicillin use. The patient had no previous history of drug allergies, including allergies to antibiotics. However, considering her overall clinical progression and long duration of penicillin use, penicillin-induced hemorrhagic cystitis was suspected. Penicillin G and ciprofloxacin were simultaneously discontinued on the 35th day. After stopping penicillin G, her frequency and dysuria improved dramatically within 2 days. The hematuria, pyuria, and eosinophilia also improved and were normalized in 8 days.

Hemorrhagic cystitis is defined as a diffuse inflammatory condition of the urinary bladder and presents with lower urinary tract symptoms that include frequency, urgency, dysuria, and hematuria. It results from damage to the bladder's transitional epithelium and blood vessels by toxins, pathogens, radiation, drugs, or disease. In most cases, drug-induced hemorrhagic cystitis resolves with discontinuation of the offending agent [1].

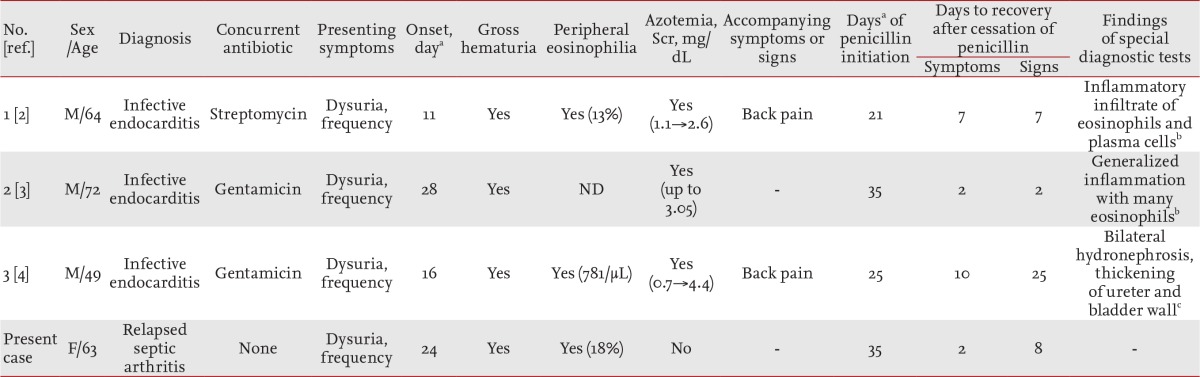

Penicillin G is reported to cause hemorrhagic cystitis on rare occasions. We used MEDLINE to retrieve previous reports of penicillin G induced hemorrhagic cystitis for all years and found three previous reports written in English. The clinical features of the three previous cases [2-4] and the present case are shown in Table 1. All previous cases were diagnosed with infective endocarditis, while our patient was diagnosed with relapsed bone and joint infection. The previous patients also underwent combination treatments with aminoglycosides for the initial 2 weeks. All patients developed the same bladder irritation symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, and gross hematuria, and two also suffered from back pain. The onset of these symptoms ranged from the 11th day to the 4th week after starting penicillin (median time, 20 days). In three cases including ours, urinalysis revealed pyuria, and urine culture was negative in all cases. Cystoscopy and bladder biopsy were performed in two cases; cystoscopy showed generally diffuse hemorrhagic cystitis, and biopsy revealed generalized inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration. Renal insufficiency (elevated serum creatinine level) was present in all cases excluding ours, and peripheral eosinophilia was present in all cases including ours. Interestingly, the urinary symptoms resolved promptly after discontinuing penicillin, and the laboratory findings returned to normal in 1 to 3 weeks in all cases. In one case [4], the patient underwent an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan instead of cystoscopy and was found to have bilateral mild hydronephrosis and thickened bladder and ureteral walls. After stopping penicillin, the hydronephrosis and hydroureter also improved. The diagnosis in our case has the limitation that we did not carry out cystoscopy, bladder biopsy, or CT. However, the clinical presentation and laboratory abnormalities were very similar to those in the previous reports. In particular, the rapid resolution of symptoms and the clinical course of recovery after discontinuing penicillin G indicate that this case was another instance of penicillin G-induced hemorrhagic cystitis.

The precise mechanism of penicillin-induced hemorrhagic cystitis is not known. It has been proposed that a penicillin-related immune reaction may damage the bladder mucosa or that penicillin itself or metabolites may be directly toxic to the bladder. Because most patients developed symptoms after prolonged exposure to penicillin, direct irritation of the bladder is a possibility. However, there is more evidence supporting an immunological basis. In three cases, peripheral eosinophilia developed, and two bladder biopsies revealed eosinophilic infiltration. In one study, a drug lymphocyte stimulation test for penicillin G was positive [4]. Moreover, immunoglobulins G and M and faint C3 deposition were seen in the bladder submucosa by immunofluorescence microscopy in the case of methicillin-induced hemorrhagic cystitis, which can be considered to involve the same mechanism as penicillin G [5].

Penicillin remains an important and useful antibiotic for the treatment of several infectious diseases. This case emphasizes that it is important to recognize hemorrhagic cystitis as an adverse reaction of penicillin because a high index of suspicion can lead to early diagnosis and withdrawal of the penicillin, without unnecessary examinations, and result in prompt recovery.

References

1. Manikandan R, Kumar S, Dorairajan LN. Hemorrhagic cystitis: a challenge to the urologist. Indian J Urol 2010;26:159ŌĆō166PMID : 20877590.

2. Cook FV, Farrar WE Jr, Kreutner A. Hemorrhagic cystitis and ureteritis, and interstitial nephritis associated with administration of penicillin G. J Urol 1979;122:110ŌĆō111PMID : 37350.

3. Adlam D, Firoozan S, Gribbin B, Banning AP. Haemorrhagic cystitis and renal dysfunction associated with high dose benzylpenicillin. J Infect 2000;40:102ŌĆō103PMID : 10762126.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print