|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 27(4); 2012 > Article |

|

Abstract

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is an uncommon disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract, which is usually associated with abdominal pain, diarrhea, ascites, and peripheral eosinophilia. Steroids remain the mainstay of treatment for EGE, but symptoms often recur when the dose is reduced. Macrolides have immunomodulatory effects as well as antibacterial effects. The immunomodulatory effect results in inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation and triggering of T-lymphocyte and eosinophil apoptosis. Macrolides also have a steroid-sparing effect through their influence on steroid metabolism. We report a rare case of EGE, which relapsed on steroid reduction but improved following clarithromycin treatment.

Macrolides have immunomodulatory effects as well as antibacterial effects. The immunomodulatory effect results in inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation and triggering of T-lymphocyte and eosinophil apoptosis [1-3]. Macrolides also have a steroid-sparing effect through their influence on steroid metabolism. A trial of macrolide therapy for bronchial asthma, which is caused by eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation, was reported to yield promising results. In the trial, blood and sputum eosinophil counts, and sputum eosinophilic cationic protein levels were significantly decreased after the administration of a macrolide. The results suggest that macrolides have a bronchial anti-inflammatory effect associated with decreased eosinophilic infiltration [4].

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is an uncommon disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract. We report a rare case of EGE, which relapsed on steroid reduction but improved following clarithromycin (CAM) treatment.

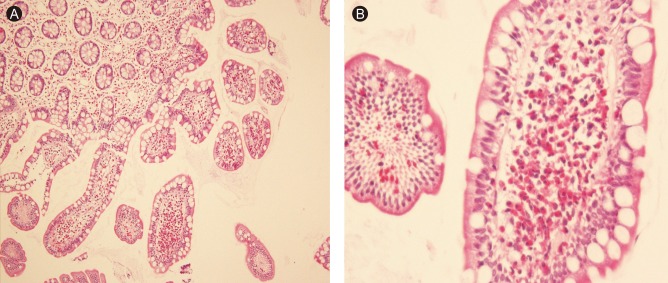

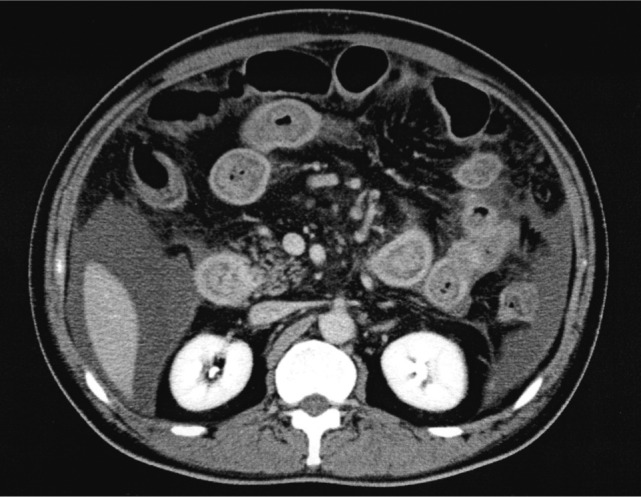

A 52-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. He had no history of food allergies or bronchial asthma. Clinical examination was unremarkable with the exception of lower abdominal tenderness. A complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 13,990/mm3 with an eosinophil count of 8,674/mm3 (62.0%). The serum immunoglobulin E level was 2,400 U/mL (normal, 6 to 90) and a radioallergosorbent test was positive for numerous allergens, including common foods. The serum level of C-reactive protein was 1.23 mg/L, and those of antinuclear antibody and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were normal. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed thickening of the small intestinal walls and ascites (Fig. 1). Endoscopic examination showed thickened and erythematous antral, duodenal, and ileal folds (Fig. 2). Biopsies of the ileum and rectum showed eosinophilic infiltration (Fig. 3). Ascitic fluid revealed an abundance of mature eosinophils against a bloody background. No malignant cells or microorganisms were identified. The final diagnosis was EGE.

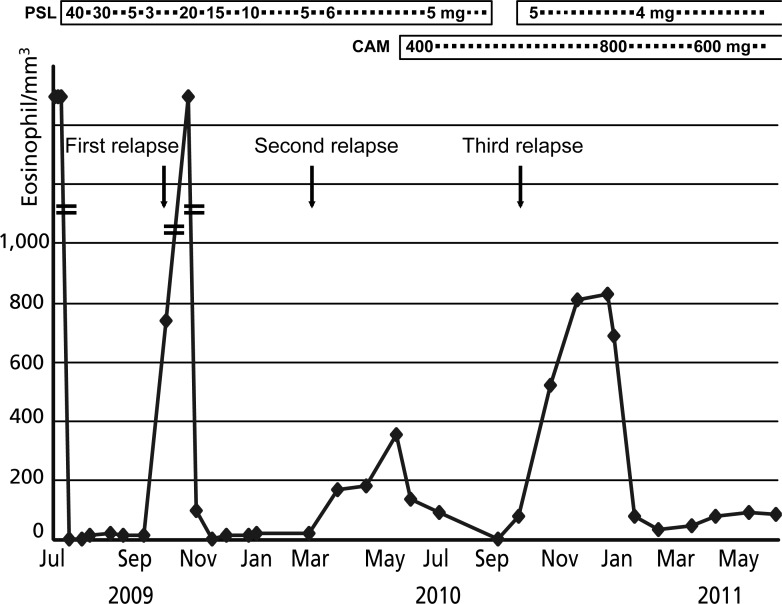

The clinical course of the disease is shown in Fig. 4. The patient was treated with prednisolone (PSL) at 40 mg/day for 2 weeks which led to a rapid improvement in the symptoms and the eosinophil counts (0/mm3). PSL was then tapered to 20 mg/day and the patient was discharged from hospital. After discharge, the PSL dose continued to be tapered uneventfully until the dose reached 3 mg/day, at which point the abdominal pain recurred and there was a rapid increase in the peripheral eosinophil counts (9,772/mm3; first relapse). The PSL dose was therefore increased to 20 mg/day, which caused a rapid improvement of eosinophilic counts (99/mm3). However, when PSL was tapered again to a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day, eosinophil counts began to increase without symptoms (second relapse). Because serum glucose levels rose to more than 200 mg/L during the PSL treatment at a dose of 10 mg/day, it was determined that the dose could only be increased to 6 mg/day. However, eosinophil counts continued to increase (351/mm3), so CAM at 400 mg/day was added after obtaining informed consent and this led to a gradual improvement of eosinophil counts (132/mm3) after 2 weeks. The intention at that point was to taper the PSL dose to 5 mg/day, but the patient was asymptomatic and therefore did not take PSL for 3 weeks because of the potential for hyperglycemia. Eosinophil counts began to increase again (521/mm3; third relapse). Although the patient was re-treated with PSL at 5 mg/day, eosinophil counts increased rapidly (829/mm3). The dose of CAM was accordingly doubled (800 mg/day), with the dose of PSL maintained at 5 mg/day. After 4 weeks, the eosinophilic count had improved (78/mm3). By the end of the observation period, the doses of PSL and CAM were reduced to 4 and 600 mg/day, respectively, with normal eosinophil counts. Follow-up enhanced CT revealed the improvement of the thickening of the small intestinal walls and ascites (Fig. 5). Long-term use of CAM did cause slightly loose stool as a side effect.

A review of the literature on treatment for EGE showed that the first step is dietary restriction [5]. It is recommended to perform skin prick testing to identify any food allergies [6]. Although an association is evident between food allergy and EGE, the results of elimination diets are often poor [6]. The next step is the use of steroids, which have been a mainstay of treatment in EGE. The dosage of PSL given at the onset of the condition is 20 to 40 mg/day for 6 to 8 weeks [6]. About 90% of patients respond to this therapy [7]. If patients require high doses of PSL for maintenance or are intolerant of steroid side effects, immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine may be helpful as steroid-sparing agents [7]. Mast cell stabilizers, such as sodium cromoglycate, that prevent the release of histamine, platelet activating factors, and leukotrienes from mast cells, have also been reported to be effective [7]. Montelukast, an antagonist of the leukotriene receptor Cys-LT1, was also found to be effective and useful as a steroid-sparing agent [8]. Other case studies have investigated the effectiveness of new interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-5 inhibitors such as suplatast tosilate [9] in EGE and anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody mepolizumab in hypereosinophilic syndromes [10].

The present case suggests that CAM was effective for the treatment of EGE. During the second relapse, when there was a gradual increase in the eosinophil count, CAM at 400 mg/day was effective in reducing the maintenance dose of PSL. During the third relapse, when eosinophil counts increased rapidly, CAM at an increased dose of 800 mg/day was effective. However, the third relapse occurred during monotherapy with CAM at 400 mg/day, suggesting that this form of treatment was not effective. The fact that CAM treatment could reduce the maintenance dose of PSL was advantageous in reducing the risk of steroid-induced hyperglycemia.

For bronchial asthma, which is caused by eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation, a trial of macrolide therapy yielded promising results. In the trial, patients received 200 mg/day of CAM for 8 weeks, after which symptoms, blood and sputum eosinophil counts, and sputum eosinophilic cationic protein levels were significantly decreased. The authors concluded that CAM had a bronchial anti-inflammatory effect associated with decreased eosinophilic infiltration [4].

Although bronchial asthma could be controlled by only 200 mg/day of CAM in that trial, a dose of 800 mg/day was needed for control of EGE during the third relapse in the present patient. This suggests that eosinophil activity is higher in EGE than in bronchial asthma.

One study showed that CAM and erythromycin (EM) suppressed the IL-5-induced prolongation of eosinophil survival in a dose-dependent manner. When eosinophils were cultured in the presence of IL-5 with physiologic concentrations of EM or CAM (both 10 µg/mL), the effect of IL-5 was almost abolished, and the morphologic changes in eosinophils observed by electron microscopy were consistent with apoptosis [3]. EM and its derivatives also inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of T-lymphocytes that secrete IL-5 [2]. In addition to immunomodulatory effects, macrolides also have steroid-sparing effects because of their influence on corticosteroid metabolism.

Study evidence suggests that the macrolide mechanism of action in treating EGE involves anti-eosinophilic effects, anti-T lymphocytic effects, and steroid-sparing effects; however, because only one case is reported, more research is necessary before this treatment can be adopted.

References

1. Ishimatsu Y, Kadota J, Iwashita T, et al. Macrolide antibiotics induce apoptosis of human peripheral lymphocytes in vitro. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;24:247–253PMID : 15325428.

2. Wu L, Zhang W, Tian L, Bao K, Li P, Lin J. Immunomodulatory effects of erythromycin and its derivatives on human T-lymphocyte in vitro. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2007;29:587–596PMID : 18075867.

3. Adachi T, Motojima S, Hirata A, et al. Eosinophil apoptosis caused by theophylline, glucocorticoids, and macrolides after stimulation with IL-5. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;98(6 Pt 2):S207–S215PMID : 8977529.

4. Amayasu H, Yoshida S, Ebana S, et al. Clarithromycin suppresses bronchial hyperresponsiveness associated with eosinophilic inflammation in patients with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2000;84:594–598PMID : 10875487.

5. Justinich C, Katz A, Gurbindo C, et al. Elemental diet improves steroid-dependent eosinophilic gastroenteritis and reverses growth failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1996;23:81–85PMID : 8811528.

6. Verheijden NA, Ennecker-Jans SA. A rare cause of abdominal pain: eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Neth J Med 2010;68:367–369PMID : 21116030.

7. Sheikh RA, Prindiville TP, Pecha RE, Ruebner BH. Unusual presentations of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: case series and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:2156–2161PMID : 19418590.

8. Quack I, Sellin L, Buchner NJ, Theegarten D, Rump LC, Henning BF. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis in a young girl: long term remission under Montelukast. BMC Gastroenterol 2005;5:24. PMID : 16026609.

Figure 2

Endoscopic examination revealing small white plaques interspersed throughout the thickened and erythematous ileal folds.

Figure 3

Histological appearance of mucosal biopsy of ileum demonstrating infiltration with eosinophils (A: H&E, × 200; B: H&E, × 400).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print