INTRODUCTION

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome is associated with anvanced malignancy and has a poor prognosis1). However, a symptomatic SVC obstruction can also be caused by benign conditions that do not affect the life expectancy of the patient. Reported cases of SVC syndrome from benign processes include the following: infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and a pyogenic infection; fibrosing processes either idiopathic or following radiation therapy; endovascular devices such as transvenous cardiac devices or indwelling catheters; vascular anomalies, aneurysms, vasculitis as well as a number of other rarer etiologies2). Here we report a case of SVC syndrome that was caused by soft tissue encircling the SVC with thrombus complications along with the accompanying CT findings using a 3-dimensional volume-rendering technique.

CASE REPORT

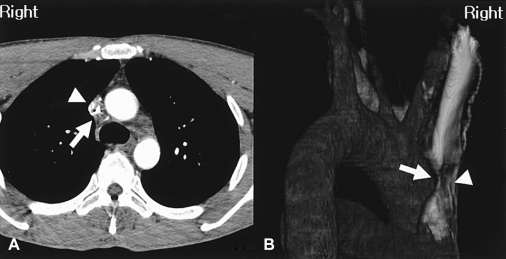

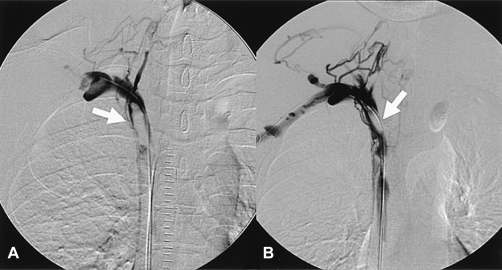

A 39-year-old man with no prior medical history presented with a four-week history of facial plethora, headache and dilated veins of the neck with a dark purple color change on the anterior chest wall. He had a normal chest radiogram and a normal blood test. Interestingly, 16-slice multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) of the chest and a 3-dimensional volume-rendering image revealed a severe narrowing of the SVC which occurred as a result of tiny encircling soft tissue and collateral vessels (Figure 1). An SVC angiogram also revealed significant luminal narrowing of the SVC (Figure 2).

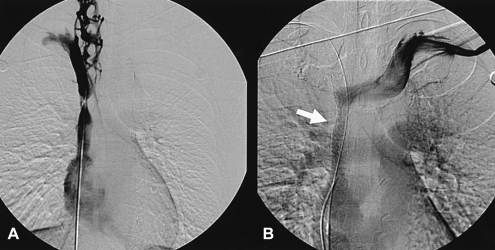

One day after the SVC angiogram, the patient complained of severe headache and facial edema. A repeat SVC angiogram revealed a thrombus at the right brachiocephalic vein and a total occlusion of the SVC (Figure 3A). A bolus of urokinase 500,000 IU was delivered through a multipurpose catheter. The follow-up SVC angiogram revealed a decrease in the size of the thrombus and distal venous flow to right atrium (Figure 3B).

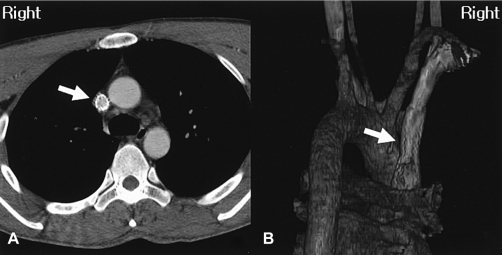

Three days later, another follow-up SVC angiogram revealed significant luminal narrowing of the SVC that was identical to the initial findings (Figure 4A). A 14 60 mm Cook Zilver stent was deployed in the SVC (Figure 4B), and the postprocedural CT revealed a wide patency (Figure 5). The patient was discharged after the facial plethora, headache and color change on the anterior chest wall had been relieved.

DISCUSSION

SVC syndrome was first described by Hunter in 17573). As reported in recent reports, 73~93% of all cases of SVC syndrome have resulted from either a primary or metastatic malignancy with the remainder of the cases due to benign disease4-6). Many benign causes have been described including fibrosing mediastinitis and iatrogenic etiologies such as sclerosis and obstructions that are caused by the use of indwelling central venous catheters2). Approximately half of the benign cases have mediastinal fibrosis6). However, the increase in the implementation of indwelling central venous catheters and permanent pacemakers has resulted in more patients with a superior vena cava obstruction with a benign etiology4).

In our case, the CT and 3-dimensional volume-rendering image showed a small amount of soft tissue encircling the SVC. It even accurately revealed the extent, level, length of stenosis, the presence of collateral vessels and could confidently differentiate other infiltrative lesions of the mediastinum, such as a lung cancer, a metastatic carcinoma, a lymphoma, and a mediastinal sarcoma. Although the focal type of fibrosing mediastinitis was strongly suspected, there was no calcified mass, which is a typical finding. Therefore, fibrosing mediastinitis could not be confidently differentiated from the other lesions and a biopsy was required. However, a histological examination could not be carried out because the patient refused surgical sampling and there was a significant risk of hemorrhage during the biopsy. In one unusual case report of localized fibrosing mediastinitis, CT and magnetic resonance (MR) images of the chest showed an intraluminal mass in the SVC without calcification7). These reported images were similar to that seen in our case except for the size of the mass. Fibrosing mediastinitis is a rare benign disorder caused by the proliferation of acelluar collagen and fibrous tissue within the mediastinum7) The SVC is most commonly involved, with the fibrosing mediastinitis causing SVC syndrome7). The precise pathogenesis and cause is unknown. However, many hypotheses have been proposed to explain this process. These explanations include an immune reaction, chronic inflammation, drugs, familial disorder, malignancy and radiation7). There are two types of fibrosing mediastinitis. The focal type usually manifests on CT or MR images as a localized, calcified mass in the paratracheal or subcarinal lesions of the mediastinum, or in the pulmonary hila8). The diffuse type manifests on CT or MR images as a diffusely infiltrating, often noncalcified mass, that affects multiple mediastinal compartments8).

It was remarkable that the thrombosis developed abruptly and a total occlusion of the SVC occurred within 1 day after the diagnostic SVC angiogram had been performed. This case is believed to be due to a procedure-related complication. After thrombolytic therapy for 3 days, the lesion recovered in a similar way to the initial lesion and a stent was deployed.

The treatment for SVC syndrome must be tailored to the underlying etiology and work quickly enough to relieve its severity or prevent life-threatening conditions. The treatment of a SVC obstruction due to a malignancy includes therapy with diuretics, steroids, and head elevation followed by chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and a subsequent endovascular procedure with angioplasty and stent placement for palliative purposes9). Therapy for a SVC obstruction due to benign causes should still be aimed at the underlying etiology. Medical therapy with anticoagulation agents might provide some relief of symptoms. However, the relief of symptoms can be accomplished by relieving the stenosis if medical therapy with anticoagulation agents alone does not sufficiently alleviative the symptoms or there is a stricture or stenosis of the SVC. Historically, this has been accomplished by surgery. However, surgery may not be tolerated by patients with unstable conditions and often fails because of a thrombosis of the surgically created graft10). It was recently reported that mid-term patency is acceptable in patients undergoing endovascular stent placement in cases of benign disease, and may be a feasible therapeutic option11).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print