INTRODUCTION

Heat stroke is a life threatening illness that's characterized by an elevated core body temperature above 40℃ with neurologic dysfunction, and it can lead to a syndrome of multiple organ dysfunction. Heat stroke can result from exposure to a high environmental temperature (the classic, nonexertional form) or from strenuous exercise (the exertional form)1). Although mild or moderate hepatic injury is common, there are only rare reports on fulminant hepatic failure with a rapid decrease in the coagulation parameters from exertional heat stroke, and fulminant hepatic failure from classical, nonexertional heat stroke has never been reported. We recently experienced a case of multiple organ failure that predominantly manifested as fulminant liver failure combined with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and acute renal failure (ARF) due to heat stroke following a warm bath. We report here on this unusual case with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old man was admitted to emergency room for loss of consciousness. He was discovered in bathtub filled with warm water and he was unconscious. He was presumed to have been in a warm bath for 3 hours at the time of discovery. He had been taking an oral hypoglycemic agent for his diabetes for 9 years.

His body temperature was 41℃, the blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg, the pulse rate was 124 beats/min and the respiratory rate was 48 breaths/min. On arrival, he was semicomatous, areflexic and flaccid, but he had no lateralizing signs or neck stiffness. His skin was hot and dry. His blood glucose was 150 mg/dL, and the arterial blood gas analysis showed a mixed high anion gap metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis (pH: 7.42, pO2: 47.2 mmHg, pCO2: 28 mmHg, and HCO3-: 18 mmol/L). On admission, laboratory findings were as follows: WBC: 6,300/L, Hb: 17.5 g/dL, platelets: 70,000/L, prothrobin time (PT): 12.8 sec (89%, INR 1.12), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT): 21.7 sec, aspartate aminotrasferase (AST): 98 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 97 IU/L, bilirubin: 0.7 mg/dL, amylase: 39 IU/L, Na/K/Cl: 140/4.1 /100 mmol/L, BUN: 32 mg/dL, creatinine: 2.3 mg/dL and myoglobin: 223 ng/mL. Brain MRI showed no hemorrhage or infarction and there was no abnormal finding on the chest X-ray.

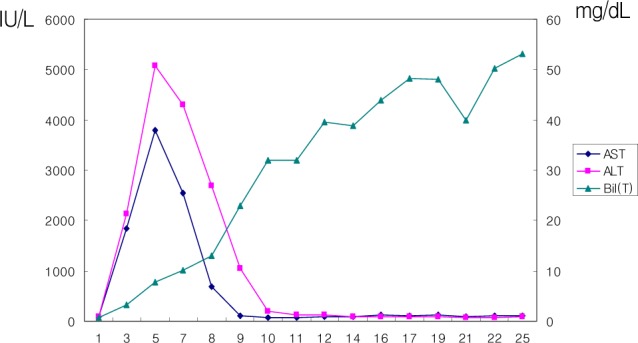

After 30 min, his body temperature was still 39.5℃. Despite further decreasing the body temperature to 38℃ via external cooling and infusion of fluids, the semicomatous mentality was not changed and so endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation were started. On day 2, the PT decreased to 13% (INR 7.57), and the aPTT was also prolonged to an uncheckable range. The AST/ALT increased to 2136/1838 IU/L and the total bilirubin increased to 3.2 mg/dL (Figure 1). The fibrinogen decreased to 185.6 mg/dL (normal range: 230-480), and the fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs) were elevated to >20 ug/dL. The laboratory findings were considered to represent acute hepatic failure combined with acute renal failure (ARF) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) following heat stroke. Other causes of fulminant liver failure like viral hepatitis and fulminant Wilson's disease were ruled out by the patient's history and/or the appropriate laboratory tests. On the third day, continuous venovenous hemofiltration (CVVHF) was started because of the progressive oligouria despite continuous infusion of diuretics and the worsening metabolic acidosis (pH: 6.93, pO2: 117 mmHg, pCO2: 41.8 mmHg and bicarbonate: 8.6 mmol/L). The serum transaminase was decreased, but the PT remained prolonged despite daily infusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The serum bilirubin level increased further to 50 mg/dL.

On day 15, abdominal distension developed and the ascitic fluid analysis showed inflammatory exudates. At the same time, Acinetobacter baumannii and Enterococcus faecium were cultured in the blood and the appropriately sensitive antibiotics were started under the impression of septic peritonitis. In spite of treatment with CVVHF and the best supportive care, the hepatic failure (bilirubin to 53 mg/dL) and DIC progressed with superimposed infection. The patient passed away on day 25.

DISCUSSION

We report here on an unusual case of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome leading to fulminant hepatic failure, ARF and DIC following a nonexertional heat stroke that was caused by a warm bath. Classical heat stroke is usually caused by exposure to sustained high temperatures, especially when the humidity is high; the most susceptible victims are elderly patients suffering with comorbid conditions such as diabetes, congestive heart failure, malnutrition or dehydration2). When the ambient temperature is higher than the core body temperature, sweating with vaporization accounts for almost all of heat loss, but when the humidity exceeds 75%, sweating becomes inefficient3). Therefore, staying in a warm bath with high humidity for a prolonged period of time could have prevented proper body heat dissipation through sweating in our patient, who also suffered from a comorbid condition of diabetes, and this resulted in a rather tragic heat stroke.

The clinical manifestations of heat stroke are variable. Brain dysfunction is invariably present and other complications that fall within the category of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome such as rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, hepatic failure, myocardial injury and DIC can be life threatening2). Although mild hepatic injury that is represented by elevated transaminase levels is known to be common, fulminant liver failure leading to a death has rarely been reported. Additionally, fulminant liver failure due to classical heat stroke has never been reported. Dematte et al. reviewed 58 cases of nearly fatal heat stroke that occurred during the 1995 heat wave in Chicago and they suggested that multisystem organ dysfunction such as acute renal failure and DIC was also common in classical heat stroke, which is similar to that reported for exertional heat stroke. However, none of the 58 patients developed fulminant liver failure4). Our patients showed the typical features of fulminant liver failure with progressive increases in the bilirubin levels and his later clinical course was complicated by infection.

The exact pathogenetic mechanisms of tissue injury are not clear, but direct thermal injury to the endothelium and the hepatocytes, tissue ischemia and/or activation of the inflammatory and coagulatory pathways have been suggested. The proinflammatory cytokine levels and the markers of endothelial injury have been reported to be elevated early in the course of heat stroke and this is thought to substantially contribute to tissue damage5).

Treatment of heat stroke consists of rapid cooling with supportive care. Previous studies have shown that decreasing the core body temperature to less than 38.9℃ within 30 min of presentation could improve survival6), but our patient's body temperature did not reach that point 30 min after presentation despite the application of external icebags and intravenous saline administration. Additionally, he had presumably been in the hot bathtub for 3 hrs and we did not know when he became semiconscious while he was in the bathtub. So, there is a possibility that the delayed cooling might have had an influence on the poor prognosis of our patient. From day 3, we started CVVHF because of the progressive oliguria and metabolic acidosis, which was presumably due to lactic acidosis from liver failure. Ikeda et. al. reported that the heat stroke patients who received blood purification had better clinical outcomes, but there has been a lack of prospective studies that can determine the role of CVVHF for the patients suffering with heat stroke7).

The most important consideration for heat stroke is its prevention. Recently in Korea and in many other Asian countries too, taking a warm bath at home is very popular and many people are enjoying it in the belief that a hot bath is useful to eliminate waste product from the body and improve the peripheral circulation. Yet staying in a bathtub in a small room with high humidity for a prolonged period of time, especially for a person who has a comorbid conditions such as diabetes or chronic heart disease that predispose him/her to the development of heat stroke is not the best idea and it could lead this kind of tragic outcome.

We report here on an unusual case of heat stroke that was due to taking a warm bath; it manifested as fulminant liver failure combined with ARF and DIC, and later by infection. Heat stroke is not a common condition, but it requires prompt recognition and immediate treatment that consists of rapid cooling followed by recognition of the organ system dysfunction and the appropriate supportive care to improve the prognosis. Persons who have predisposing conditions should be warned about taking a too hot a bath for too long because it can result in needless morbidly or morality.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print