INTRODUCTION

The natural history of Graves' disease is altered during pregnancy due to the patient's immunologic changes. Amelioration of the disease's symptoms in the second half of pregnancy with aggravation during the postpartum period is common1). Therefore, an outbreak and relapse of Graves' disease in the second trimester of gestation is rare. Agranulocytosis is a well known side effect of antithyroid drugs. Although thionamide induced agranulocytosis can be a life threatening condition, it is rare2). We were recently presented with a pregnant woman experiencing a relapse of Graves' disease that was complicated by propylthiouracil induced agranulocytosis. Management of this complicated case was very difficult because a successful outcome was desired for both the mother and the fetus. Therefore, we report here on our case with a review of the treatment options.

CASE REPORT

A 28-year-old woman in her 24th week of pregnancy visited our hospital experiencing febrile sensation and palpitation. The woman was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism 10 years earlier and had taken thionamide periodically. She had not taken any medication recently because she did not display any signs or symptoms of hyperthyroidism. At the 20th week of gestation, she had a relapse of hyperthyroidism and resumed taking the thionamide (propylthiouracil 300 mg) that she had received at a local clinic. At that time, her blood count was within the normal range.

At her initial visit to the hospital, her blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate 110/min,respiratory rate 23/min and body temperature 39Ōäā. Her height and body weight were 163 cm and 55 kg. On physical examination, the patient was alert, her heart rhythm was regular and there was no sign of a murmur. She had a diffuse goiter and mild ophthalmopathy, and there was no evidence of any upper respiratory tract infection.

Her full blood count showed total WBCs at 1,600/mm3 with neutrophils 213/mm3 and lymphocytes 963/mm3, platelets 233├Ś103/mm3 and hemoglobin 9.1 g/dL. Level of free T4 was 5.7 ng/mL (0.7~1.9), total T3 was 6.51 ng/mL (0.6~1.7), and TSH was<0.005 mU/mL (0~4.7). TBII (TSH-binding inhibitory immunoglobulin) was 61% (< 14.9%). AST/ALT were 49/47 IU/L and BUN/Creatinine were 12/1.0 mg/dL. An EKG showed sinus tachycardia and chest X-rays were normal. A fetal ultrasound examination revealed a normal sized fetus for the gestation period. The fetal heart rate was 160 beats/min and a non-stress test showed a reactive response.

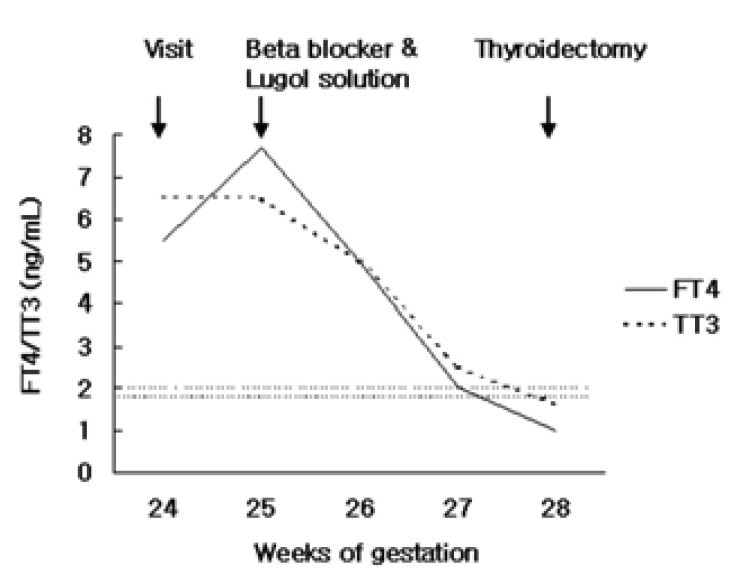

Following the discontinuation of propylthiouracil, we began intravenous antibiotics (cephalosporin) and hydration (5% sodium dextrose fluid). Due to the possibility of teratogenecity, we excluded the use of G-CSF (granulocyte-colony stimulating factor). The patient's neutrophil count recovered to normal range with supportive care and her fever resolved after 10 days, yet her symptoms of hyperthyroidism were aggravated. At this point it was difficult to choose the optimal treatment method which would save both the mother and fetus. After considering all treatment options, it was decided that a total thyroidectomy rather than a subtotal thyroidectomy was the better option in this case, in order to prevent any future relapse. We also prescribed a beta-adrenergic blocker (propranolol 80 mg/day) and a Lugol solution (5% Lugol solution 1.2 mL/day) because a thyroidectomy without preoperative management was viewed to be too risky due to the high risk of thyrotoxic crisis. The treatment consisting of the beta-adrenergic blocker and the Lugol solution led to a rapid decline ofserum free T4 and total T3 concentration back to their normal ranges within 2 week (Figure 1). At 28 weeks of gestation, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy without complications. Thyroxine replacement began on the first day following the operation and the patient's thyroid hormone levels were normalized after levothyroxine (synthyroid) 0.2 mg replacement.

The maternal TBII level at 38 weeks of gestation decreased to 23% and labor was induced at 40 weeks. A 3,370 g healthy male infant was born without any clinical features of thyrotoxicosis.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of hyperthyroidism in pregnant women has been reported to be in the range of 0.05 to 0.2%, and Graves' disease is known to be the major cause of hyperthyroidism in pregnant women1). However, severe hyperthyroidism and aggravation of Graves' disease, as was seen in our case, is rarely seen during pregnancy because Graves' disease usually follows a mild course in pregnant women due to the decreased aggressiveness of autoimmune mechanisms1).

For pregnant women with hyperthyroidism, preeclampsia and heart failure have frequently been reported. Davis et al3) reported that preeclampsia and/or heart failure have been observed in 5 of 8 pregnant hyperthyroid women for whom antithyroid treatment began only after parturition. In addition, pregnancy complicated by hyperthyroidism is also recognized as a cause of impaired fetal outcome. Momotani and Ito4) observed that hyperthyroidism at the time of conception was complicated 25.7% of the time by spontaneous abortion and 14.9% of the time by premature delivery in comparison with 12.8% and 9.5%, respectively, for pregnant women who were euthyroid. It is uncertain whether untreated Graves' disease is associated with a higher frequency of congenital abnormalities. However, Momotani and Ito4) observed that such congenital malformations as anencephaly, imperforate anus and harelip have been reported with an incidence of 6% for newborns of untreated pregnant hyperthyroid women, whereas no congenital malformations were observed for neonates whose mothers were euthyroid after treatment with propylthiouracil or methimazole. Therefore, in order to avoid the problems related to hyperthyroidism, immediate and appropriate treatment has to be commenced for pregnant women with uncontrolled hyperthyroid.

The antithyroid drug thionamide is the therapy of choice for pregnant women. Propylthiouracil is more favorable for pregnant women because there is less potential fetal transfer and because of the concerns over the possible association of methimazole with aplasia cutis and choanal atresia1). Serious side effects such as hepatitis, an SLE-like syndrome, and, most importantly, agranulocytosis (a granulocyte count < 500/mm3) are uncommon with the use of thionamides, and these illnesses are observed in approximately 3 of every 1000 patients5). Therefore, the occurrence of thionamide-induced agranulocytosis in pregnant women is very rare. General treatment of agranulocytosis includes prompt discontinuation of the antithyroid drug and administration of a broad-spectrum of antibiotics and growth factors to stimulate bone marrow recovery5). However, management of agranulocytosis in pregnant women requires careful consideration of the available options and risks to bothmother and fetus. Studies have shown G-CSF induce an accumulation of neutrophils in the vessels of the placenta and cause embolism in pregnant rabbits. Therefore, G-CSF is known to increase abortions and fetal mortality6). Because of this concern, we excluded the use of G-CSF in our patient.

To treat the patient's hyperthyroidism, reintroduction of thionamide drugs is regarded as risky. Therefore, an alternative treatment is usually required, and most often this is radioiodine or a thyroidectomy1). However, radioiodine is contraindicated in pregnancy. Surgery has been successful in treating pregnant hyperthyroid women. The optimal timing for the thyroidectomy depends on balancing the risks of fetal loss against those of uncontrolled maternal hyperthyroidism. Surgery in the first and third trimesters of the pregnancy is associated with a high risk of spontaneous abortion. Therefore, a thyroidectomy in the second trimester is preferred7). In this case, the thyroidectomy was not delayed because agranulocytosis developed at the second trimester. However, if such complications occurred in first or third trimester, it would have been more difficult to manage this patient. Subtotal thyroidectomies have for a long time been the surgery of choice for Graves' disease. Many patients remain euthyroid following a subtotal thyroidectomy but they are at the risk of possible future thyrotoxicosis relapse7). In spite of the development of hypothyroidism, total thyroidectomies have only been performed in a few studies8-10), with the aim of avoiding future relapses of hyperthyroidism and the possible worsening of thyroid associated ophthalmopathy. Miccoli et al.10) compared the outcome of two groups of patients with Graves' disease who underwent total and subtotal thyroidectomies. A total thyroidectomy did not present more complications when compared to a subtotal thyroidectomy, but it did avoid worsening of thyroid humoral autoimmunity and the relapse of hyperthyroidism. Therefore, we chose to perform a total thyroidectomy in order to eliminate the small possibility of a future relapse.

In addition, we considered many preoperative options because a thyroidectomy with the patient not in a euthyroid state was viewed to be too risky due to the high risk of thyrotoxic crisis. Long-term treatment with beta-adrenergic blocking agents, mainly propranolol, is not recommended for pregnant patients because of the increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation, abortion, fetal bradycardia and perinatal hypoglycemia11). However, beta-adrenergic blockers can generally be used safely for a few weeks, mainly before a thyroidectomy, in pregnant hyperthyroid women12). The use of iodides during pregnancy is usually contraindicated because of their association with neonatal goiter and hypothyroidism13). However, giving iodides for a short period of time in preparation for surgery or for the management of a thyrotoxic crisis did not seem to put the fetus in any additional danger. Momotani N et al14) administered iodide, 6~40 mg per day, to a group of mildly hyperthyroid women during pregnancy, with the majority being in the third trimester. The results of the thyroid tests showed levels maintained at the upper limit of normal or at a mildly hyperthyroid range. The fetal outcome for the women was normal with no evidence of neonatal goiter. Therefore, we decided to use a short course treatment of a beta-adrenergic blocker and the Lugol solution for the preoperative management. The treatment was successful and the patient achieved a euthyroid state.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print