|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 24(4); 2009 > Article |

|

Abstract

Etanercept is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor that has been used for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Because of its immunosuppressive activity, opportunistic infections have been noted in treated patients, most notably caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis may present in an extrapulmonary or disseminated form. Since TNF-╬▒ inhibitors have been used in Korea, a few cases of TNF-╬▒ inhibitor associated tuberculosis have been described. However, tuberculous arthritis has not been previously reported. We describe a case of tuberculous arthritis in a 57-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis who was treated with etanercept.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of a variety of autoimmune diseases. The biologic effects of TNF-╬▒ include the mediation of systemic inflammatory responses as well as the response to a variety of infections, particularly Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other intracellular pathogens [1]. TNF-╬▒ also stimulates the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the formation of granulomas [2,3].

TNF-╬▒ inhibitors have demonstrated clinical benefit in the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis and Crohn's disease [4]. Occasionally, these agents have been associated with infectious complications [5,6]. TNF-╬▒ inhibitors have been suggested to increase the risk of tuberculosis; this is not surprising considering the role of TNF-╬▒ in the defense mechanisms against mycobacterium [7]. Therefore, physicians must be vigilant in the prevention and early detection of tuberculosis, in patients that receive TNF-╬▒ inhibitors, particularly with unusual manifestations of the disease.

Although several complications have been described following treatment with TNF-╬▒ inhibitors, tuberculous arthritis has not been reported previously in Korea [8]. We describe a 57-year-old woman who developed severe tuberculous arthritis in the elbow joint following etanercept administration for RA.

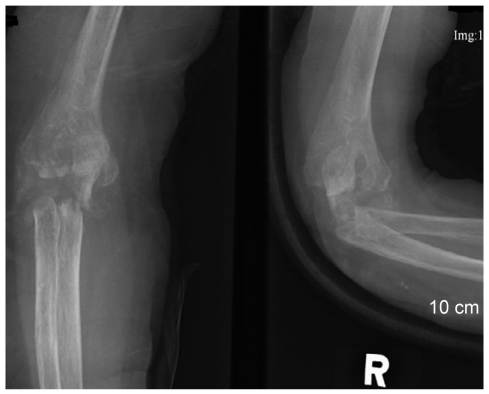

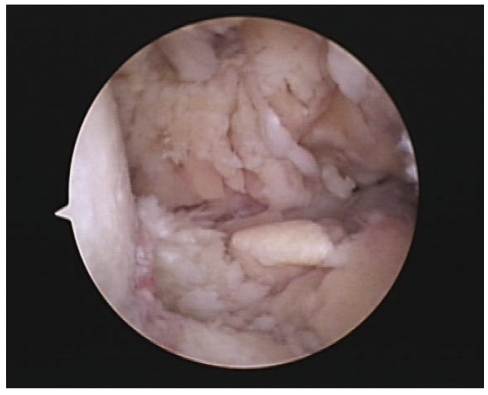

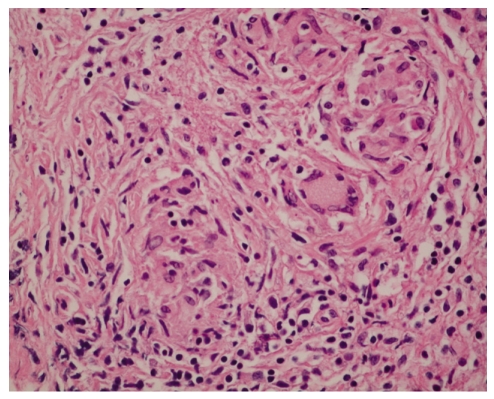

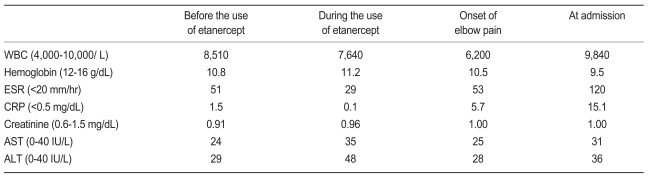

A 57-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital because of swelling, pain and warmth noted at the right elbow. The patient had seropositive RA diagnosed 15 years ago. The involved joints included wrist, elbow, knee, and ankle, bilaterally. She underwent bilateral knee arthroplasty 9 years previously and right ankle arthrodesis 2 years ago. Recently, the patient was treated with naproxen, prednisolone, methotrexate and cyclosporine A. Despite treatment, the symptoms remained active. Three months prior to admission she was started on etanercept injections (25 mg, twice weekly) combined with methotrexate, prednisolone and aceclofenac. A purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test performed before administration of etanercept was negative with 3 mm induration and a chest X-ray revealed no evidence of tuberculosis. The patient did not have a history of tuberculosis nor any known exposure to persons with active tuberculosis. The articular symptoms improved gradually after the etanercept injections. The serial laboratory tests showed improvement during the use of etanercept (Table 1). However, one month before admission, the patient began to experience swelling and pain of the right elbow joint. Intermittent fever and anorexia were also reported to be present. Her temperature was 38Ōäā, blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, and pulse 80/minites. Physical examination revealed swelling with moderate tenderness and local heat around the right elbow. The range of motion was very limited. There was no lymphadenopathy. Chest and abdominal examinations were normal. Laboratory evaluation showed an increase in acute phase reactants. Renal and liver function tests were normal (Table 1). Blood and urine cultures were negative. The aspirates from the elbow joint showed cloudy yellow fluid with a white blood cell 75,000/mm3 (95% of neutrophil). Gram staining of the synovial fluid revealed no bacteria. A chest radiograph demonstrated no new infiltrates. Plain radiography of the elbow joint disclosed extensive osteolytic bony destruction (Fig. 1). Arthroscopic debridement and synovectomy were performed. Severe inflammatory changes in the synovium with destruction of cartilage and subchondral bone were noted (Fig. 2). Pathology examination of the biopsy specimen revealed numerous granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and giant cells (Fig. 3). Eventually, cultures of the joint tissue specimen and joint fluid grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was treated with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. The treatment with etanercept was discontinued. Three weeks later, there was significant decrease in the swelling and tenderness over the joint. The elbow discomfort continues to improve.

TNF-╬▒ stimulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines and influences the maturation of inflammatory cells [5]. It promotes recruitment of inflammatory cells to the area of infection, and stimulates the formation and maintenance of a granuloma. In addition, TNF-╬▒ directly activates macrophages, which engulf and kill the mycobacterium and other pathogens. Thus, it is a key component of host defenses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis [2]. TNF-╬▒ acts in a number of ways to influence the course of an infection. Early in the process, TNF-╬▒ promotes the influx of cells into the infected area to control the inciting agent, and later it helps to limit the extent of damage by inducing apoptosis and maintaining granuloma formation [2]. However, these functions may be disturbed in the presence of a TNF-╬▒ inhibitor, making the host vulnerable to tuberculosis [9,10].

At present, three types of TNF-╬▒ inhibitors are available in Korea: infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab. These agents have been recommended as treatment for RA in patients who are not adequately controlled by at least two other disease modifying anti-rheumatic agents [1,11]. Etanercept is a fusion protein that consists of two soluble p75 TNF-╬▒ receptors linked to an immunoglobulin Fc domain. It functions as a soluble receptor of TNF-╬▒, competing with TNF-╬▒ on the cell membrane receptors and blocking the biological activity [12,13]. Its efficacy is demonstrated within the first week of treatment and tends to be sustained throughout the duration of therapy. Several side effects have been reported, including injection site reactions, headache, demyelinating disorders, lupus, and infections [6].

Use of TNF-╬▒ inhibitors have been implicated in the reactivation of tuberculosis or in the progression of recently acquired tuberculosis. In a recent report, Mohan et al. [14] reviewed 25 cases of tuberculosis in patients who were treated with etanercept. Thirteen (54%) patients were diagnosed with extrapulmonary tuberculosis, including three cases of disseminated disease, two of lymphadenitis and one with articular tuberculosis. These atypical clinical presentations may result in a delay of diagnosis and treatment.

Tuberculous arthritis commonly presents with chronic pain accompanied by swelling and progressive loss of joint function [15]. The diagnosis is often delayed, especially if it involves the same joints affected by RA. The typical radiological findings are periarticular osteoporosis, peripherally located bony erosions, gradual narrowing of the joint space, and periarticular bone destruction [16]. In this case, the plain film showed extensive bony destruction, which prompted us to perform an invasive procedure. The identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential for the diagnosis of tuberculous arthritis. However, acid-fast stains of the synovial fluid smears are positive in only 20-25%. On the other hand, cultures of joint fluid are positive in about 90% of cases [15]. The diagnosis in this patient was established by isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the culture of the synovial tissue and joint fluid and the histological findings of the synovium. The therapy for articular tuberculosis is the same as for other forms of tuberculosis. If the patient is not responding to drug therapy, synovectomy, debridement, joint arthrodesis, or joint replacement may be considered [15].

The risk of reactivation of tuberculosis by a TNF-α inhibitor depends on many factors including the underlying immune status of the patient and the immunomodulating effects of the therapy. In patients with RA, the use of corticosteroids has been associated with an increased risk of tuberculosis, presumably due to its effects on cell-mediated immunity [17,18]. Physicians should be aware of the increased risk of reactivation of tuberculosis in patients who are receiving a TNF-α inhibitor and, in particular, of the unusual clinical manifestations. Assessment of the risk factors and the PPD test are recommended to determine the presence of latent tuberculosis and the risk for active disease [19-21]. Individuals with positive PPD tests must be thoroughly assessed for active tuberculosis. Active tuberculosis must be treated appropriately before initiation of TNF-α inhibitor therapy. Patients with a positive PPD test, without evidence of active tuberculosis, should have the anti-TNF agent withheld until the patient has been adequately treated for at least one month. To screen and treat patients with evidence of latent tuberculosis infection, the PPD skin test may be insufficient. In addition, there can be some difficulty evaluating the results as a false-positive in patients who received a BCG vaccination. Recently, the introduction of a whole blood interferon (IFN)-γ assay, QuantiFERON®-TB Gold test (Cellestis, Victoria, Australia) or T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, UK) may add to the accuracy for the detection of latent tuberculosis. However, there are limited data on the use of whole blood IFN-γ assays in immunosuppressed subjects. By contrast, PPD skin tests may have false-negative results in immune compromised or severely ill patients; meticulous assessment of the risk of tuberculosis should be performed in every patient. Furthermore, many patients with RA treated with immunosuppressive therapy, can have false-negative results on PPD tests. Chest radiography is a useful tool for screening active tuberculous infection. As the use of TNF-α antagonists becomes more widespread, additional cases of tuberculosis associated with TNF-α inhibitor treatment are expected. If infection does develop, early detection and appropriate treatments are mandatory to obtain a good outcome.

References

1. Papadakis KA, Targan SR. Tumor necrosis factor: biology and therapeutic implications. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1148ŌĆō1157PMID : 11040201.

2. Algood HM, Lin PL, Flynn JL. Tumor necrosis factor and chemokine interactions in the formation and maintenance of granulomas in tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41(Suppl 3):S189ŌĆōS193PMID : 15983898.

3. Roach DR, Bean AG, Demangel C, France MP, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection. J Immunol 2002;168:4620ŌĆō4627PMID : 11971010.

4. Taylor PC. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2001;13:164ŌĆō169PMID : 11333343.

5. Ellerin T, Rubin RH, Weinblatt ME. Infections and anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3013ŌĆō3022PMID : 14613261.

6. Hamilton CD. Infectious complications of treatment with biologic agents. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:393ŌĆō398PMID : 15201602.

7. Gardam MA, Keystone EC, Menzies R, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and tuberculosis risk: mechanisms of action and clinical management. Lancet Infect Dis 2003;3:148ŌĆō155PMID : 12614731.

8. Seong SS, Choi CB, Woo JH, et al. Incidence of tuberculosis in Korean patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): effects of RA itself and of tumor necrosis factor blockers. J Rheumatol 2007;34:706ŌĆō711PMID : 17309133.

9. Listing J, Strangfeld A, Kary S, et al. Infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3403ŌĆō3412PMID : 16255017.

10. Winthrop KL, Siegel JN, Jereb J, Taylor Z, Iademarco MF. Tuberculosis associated with therapy against tumor necrosis factor alpha. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2968ŌĆō2974PMID : 16200576.

11. Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1594ŌĆō1602PMID : 11096166.

12. Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor: Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999;340:253ŌĆō259PMID : 9920948.

13. Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:478ŌĆō486PMID : 10075615.

14. Mohan AK, Cote TR, Block JA, Manadan AM, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis following the use of etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:295ŌĆō299PMID : 15306993.

15. Gardam M, Lim S. Mycobacterial osteomyelitis and arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2005;19:819ŌĆō830PMID : 16297734.

16. De Backer AI, Mortele KJ, Vanhoenacker FM, Parizel PM. Imaging of extraspinal musculoskeletal tuberculosis. Eur J Radiol 2006;57:119ŌĆō130PMID : 16139465.

17. Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, et al. Risk and case characteristics of tuberculosis in rheumatoid arthritis associated with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Sweden. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1986ŌĆō1992PMID : 15986370.

18. Gomez-Reino JJ, Carmona L, Valverde VR, Mola EM, Montero MD. BIOBADASER Group. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may predispose to significant increase in tuberculosis risk: a multicenter active-surveillance report. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2122ŌĆō2127PMID : 12905464.

19. American Thoracic Society (ATS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:S221ŌĆōS247PMID : 10764341.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print