INTRODUCTION

Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a proliferative disease characterized by monoclonal proliferation and the infiltration of organs with Langerhans' cells [1]. Several organ systems may be involved in LCH including the lungs, bone, skin, pituitary gland, liver, lymph nodes, and thyroid [1]. Localized forms of LCH in bone have been referred to as eosinophilic granuloma since Lichtenstein first described them in 1940 [2]. The term "pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (PLCH)" was first coined by Farinacci in 1951 [3] and refers to disease in adults that affects the lungs, either in isolation or in addition to other organ systems [3]. Multi-systemic variants of this disease are known by a variety of names, including systemic histiocytosis X, Letterer-Siwe disease, and Hand-Schuller-Christian disease [4]. To avoid confusion, the Histiocyte Society has established a simplified classification system [5]. According to this system, PLCH is a disease in adults that affects the lungs, either in isolation or in addition to other organ systems [5].

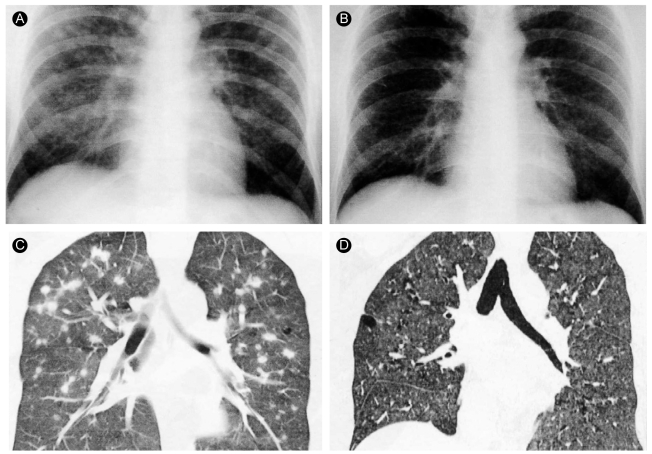

The most common findings on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest are multiple nodular and cystic changes, which occur predominantly in the middle and upper lobes [6,7]. Nodular lesions are predominant in the early stage of PLCH and progress to cystic lesions in later stages of the disease [8]. In Korea, multiple cystic lesions are the main radiological findings of PLCH, and no cases with multiple nodular lesions without cysts have been reported [9,10]. Here, we report a case of PLCH with multiple nodules without cysts throughout the lungs.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old male was admitted to our hospital for a cough and exertional dyspnea, which had been present for 2 months. He had no hypertension, tuberculosis, or diabetes, and no history of surgery, medication, or travel. He was a current smoker and a social drinker. He did not appear ill, and his mental state was normal. His vital signs were blood pressure 120/80 mmHg, pulse 84/minites, respiration rate 20/minites, and body temperature 37.2℃. Physical examination of the head and neck revealed no palpable cervical lymph nodes or masses and no neck vein engorgement. Auscultation of the chest revealed a regular heart beat with no murmurs and clear breath sounds with no crackles or wheezing. The abdomen was soft and flat, with no palpable mass or tenderness. Physical examination of both extremities showed no finger clubbing, cyanosis, or edema.

Laboratory examination indicated a white blood count of 10,310/mm3, hemoglobin concentration of 16.0 g/dL, and platelet count of 202,000/µL, and the chemistry was unremarkable. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.455, PaO2 99.1 mmHg, PaCO2 38.2 mmHg, HCO3 27 mmol/L, and 98% O2 saturation. The results of the pulmonary function test were forced vital capacity (FVC) 5.46 L/minites (105% of predicted), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) 4.59 L/minites (110% of predicted), and FEV1/FVC 84%. We performed fiber optic bronchoscopy for bronchoalveolar lavage and observed no abnormal findings in the Gram stain or culture, acid-fast bacillus stain or culture, tuberculosis-PCR, or cytology.

Chest radiography revealed multiple nodular opacities in the upper and middle lungs (Fig. 1A). The chest CT revealed variable-sized nodules with peribronchiolar or centrilobular distribution, some of which revealed thick-walled cavitary change (Fig. 2). The differential diagnosis based on the chest CT findings was that the pulmonary nodules represented hematogenous metastasis.

We performed an open lung biopsy at the right middle and lower lobe. Histologically, multiple nodules showed an infiltration of eosinophils, lymphocytes, and Langerhans' cells (Fig. 3A). These cells stained with S-100 protein and were compatible with LCH (Fig. 3B).

Treatment consisted only of smoking cessation, and a chest radiograph 4 months later indicated that the nodules had decreased in size. After 15 months, we observed that the symptoms had improved further, and a follow-up chest radiograph and HRCT indicated that the multiple nodules had disappeared (Fig. 1D).

DISCUSSION

This case involved a young male who currently smoked and had multiple pulmonary nodules, which were suspicious of metastasis. However, the results of a biopsy indicated PLCH. PLCH is a rare disorder found in only 5% of biopsy-confirmed interstitial lung disease [1]. Vassallo et al. [1] reviewed 102 cases with histopathologically confirmed PLCH drawn from a group with a mean age of 40.3 years and a 1 : 1.5 ratio of males to females and found that 95% of the cases involved smokers. Common symptoms included a cough, dyspnea, and occasionally chest pain [1].

No known genetic, occupational, or geographic risk factors are associated with PLCH. The only consistent epidemiologic association is cigarette smoking, which is involved in the overwhelming majority (>90%) of cases [1,10]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the association between cigarette smoking and PLCH. According to one, cigarette smoke induces the secretion of bombesin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the lungs [11]. These peptides may have an important role in mediating lung injury and consequently induce lung fibrosis [11]. Other components of cigarette smoke, such as tobacco glycoprotein, have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of PLCH [12]. Tobacco glycoprotein is an immunostimulant that induces lymphocyte differentiation and lymphokine production [12]. Nevertheless, PLCH occurs in a very small percentage of smokers, so genetic or environmental factors likely contribute to the development of this disease. A young male who currently smoked complained of a cough and exertional dyspnea, common clinical features of PLCH; however, the radiological findings did not support a diagnosis of PLCH.

HRCT of the chest is a useful, sensitive tool in the diagnosis of PLCH [1,13]. The combination of diffuse, irregularly shaped cystic spaces with small peribronchiolar nodular opacities, predominantly in the middle and upper lobes, is highly suggestive of PLCH [6-8,13]. When these features are present on HRCT, they allow the clinician to make a diagnosis of PLCH without a lung biopsy [1]. The lung cysts of PLCH are often less than 20 mm in diameter and typically have thin walls (<1 mm) [6-8]. The frequency of cystic change reflects the timing of imaging during the course of the disease [1,6-8]. In the early stages, the most common finding is nodular change, whereas in the later stages, cystic change and fibrosis predominate [6-8].

Based on the radiological staging, this case represents an early stage of PLCH comprised of nodular lesions only without cystic change. This finding is rare; only one other case of PLCH with multiple cavitating pulmonary nodules has been reported [13], although several cases of PLCH presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule have been reported worldwide [14]. None of these cases progressed to a more severe stage, such as cystic change or reduced pulmonary function [15]. Brauner et al. [8] reported two cases of PLCH in which only nodules were present: one progressed to cystic change and the nodular lesion disappeared in the other. It is thought that predominantly nodular lesions in PLCH appear early in the reversible state of the disease. In Korea, a number of cases of PLCH have been reported based on variable radiological findings, including multiple cysts and a combination of nodules and cysts [9,10]. However, no case involving only nodular lesions has been reported. Atypical radiological findings as in this case need to be followed to determine whether sarcoidosis, pneumoconiosis, military tuberculosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or metastatic lung nodules are present. The confirmative diagnostic tool is a pathological examination of a lung biopsy. In this case, an open lung biopsy was performed, which resulted in the diagnosis of PLCH based on positive staining for S-100 protein. The only treatment was smoking cessation, and clinical and radiological improvement was observed 15 months later. This suggests that the nodular lesions of the PLCH were in the reversible stage.

Here, we report a case of early stage PLCH in a young male that had atypical radiological features, which consisted of variable-sized nodules only without cystic changes.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print