|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 24(3); 2009 > Article |

|

Abstract

The gene responsible for nail-patella syndrome, LMX1B, has recently been identified on chromosome 9q. Here we present a patient with nail-patella syndrome and an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. A 17-year-old girl visited our clinic for the evaluation and treatment of proteinuria. She had dystrophic nails, palpable iliac horns, and hypoplastic patellae. Electron microscopy of a renal biopsy showed irregular thickening of the glomerular basement membrane. A family history over three generations revealed five affected family members. Genetic analysis found a change of TCG to TCC, resulting in a synonymous alteration at codon 219 in exon 4 of the LMX1B gene in two affected family members. The same alteration was not detected in an unaffected family member. This is the first report of familial nail-patella syndrome associated with an LMX1B in Korea mutation, However, we can not completely rule out the possibility that the G-to-C change may be a single nucleotide polymorphism as this genetic mutation cause no alteration in amino acid sequence of LMX1B.

Nail-patella syndrome (NPS) is a highly penetrant, autosomal-dominant hereditary disorder that exhibits variable expression within and among families. The condition is pleiotropic and affects tissues of both ectodermal and mesodermal origin. Manifestations include symmetrical nail, skeletal, ocular, and renal anomalies [1]. Triangular lunulae at the base of the nails and longitudinal nail ridges are characteristic of NPS. Skeletal abnormalities include absent or hypoplastic patellae, triangular bony protuberances of the posterior ilium (iliac horns), and contractures of other joints [2,3]. Nephropathy manifests with proteinuria or intermittent nephritic syndrome; in 8-10% of cases, renal problems will progress to renal failure and can be a serious complication in some families [4,5]. Recent evidence suggests that open-angle glaucoma may also be part of the syndrome [6].

Linkage studies have refined the location of the NPS gene to a 1-2 cM interval at 9q34, and a LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, has been mapped to the same general location [7]. This disorder has recently been shown to be caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain transcription factor (LMX1B), which is required for the normal development of dorsal limb structure, the glomerular basement membrane, the anterior segment of the eye, and dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons. Although to date no obvious correlation has been established between LMX1B mutations and the range and severity of NPS symptoms, many studies continue to identify associations between clinical features and a variety of LMX1B mutations. These efforts allow the examination of interactions between LMX1B and other factors that regulate development of the human limb, eye, and nervous system.

No studies have previously reported mutation analyses of NPS in Korean patients. In this report, we present the identification of a genetic alteration in the LMX1B gene found in a Korean family with NPS.

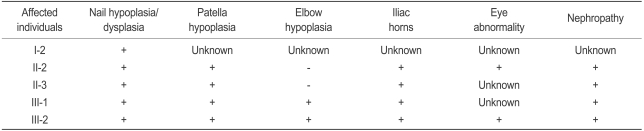

The family history revealed no known consanguinity among the patients, who reside in different regions of Korea (Fig. 1). The pedigree constructed comprises seven members of three generations. Summaries of physical findings for each member at the time of genetic testing are presented in Table 1. Five affected members were identified: one on the basis of anamnestic data (probable disease) and four after reviews of medical records and physical examinations (diagnosed disease). All three generations evaluated had family members with NPS.

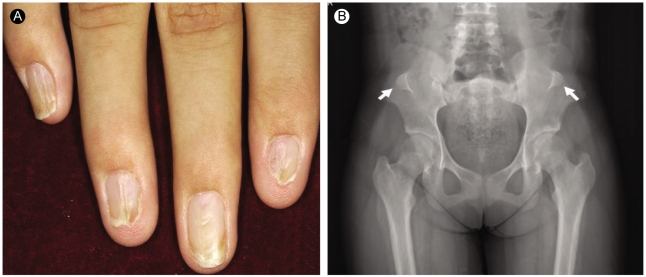

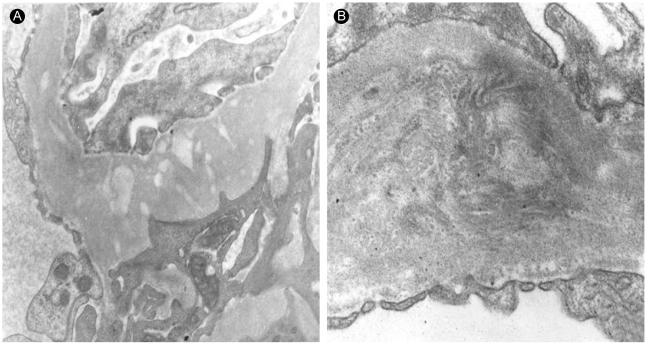

The proband (III-2) was referred for nephrological assessment due to proteinuria. Physical examination showed nail changes, including spooning, roughening of the nail plate, longitudinal ridges, and hypoplasia of the midportion of the nails, which were prominent on the thumbs and index fingers (Fig. 2A); decreased range of movement at the elbows with mild antecubital webbing; a restricted range of motion (from 0° to 135°) with some crepitation in both knees, and laterally subluxed patellae; and palpable posterior iliac horns. Standard radiographs of the elbow revealed hypoplasia of the radial epiphysis; in addition, mediolateral radiographs of the knee joint showed that both patellae were hypoplastic. Pelvic radiography confirmed the presence of bilateral posterior iliac horns (Fig. 2B). On ophthalmologic examination, the patient excretion had open-angle glaucoma and trabeculodysgenesis. Urinalysis showed 3+ proteinuria, and 24-hour urine protein was elevated 476 mg/ 24-hours. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine were both normal. On renal biopsy, the glomeruli appeared normal under light microscopy, and immunofluorescence microscopy was negative for immunoglobulin, complement components, and fibrinogen. Electron microscopy revealed prominent thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, with irregular, sharply defined rarefied areas, which gave rise to a pathognomonic "moth-eaten" appearance. After phosphotungstic acid staining, dark fibrillar collagen bundles were observed within the rarefied areas of the glomerular basement membrane (Fig. 3).

After obtaining written informed consent, we performed a genetic analysis of three members of the family shown in Fig. 1. DNA from two affected individuals (II-2, III-2) and an unaffected family member (II-1) were analyzed for the presence of LMX1B mutations. The other two affected members (II-3 and III-1) refused genetic analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood leukocytes using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The region encoding eight exons of the LMX1B gene was amplified from the genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a previously described primer pair [8]. Subsequently, PCR products were sequenced using an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the forward and reverse primers from the PCR amplification. The sequencing was performed on an ABI 3700 automated sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems). Data were collected and analyzed using the ABI DNA sequence analysis software (version 3.6; PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

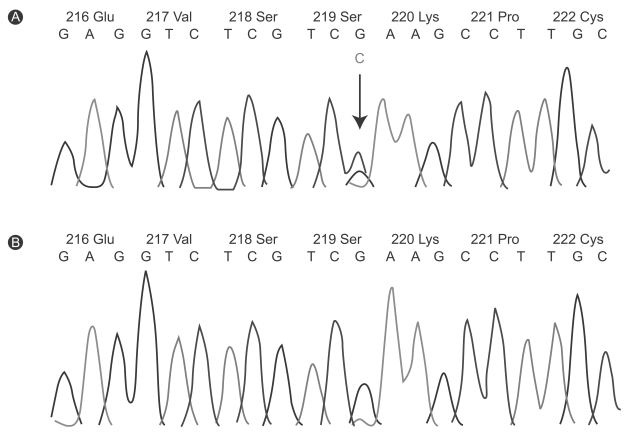

DNA analysis of the patients (III-2, II-2) showed a single-nucleotide change of TCG to TCC, resulting in a synonymous alteration at codon 219 in exon 4 of the LMX1B gene (Fig. 4A). No other abnormalities were found in the exons analyzed. The same alteration was not detected in one patient's unaffected uncle (II-1; Fig. 4B).

Conformational changes in the LMX1B gene would be expected to result in the dysfunction of normal patterning in the dorsoventral axis of the limb and in early morphogenesis of the glomerular basement membrane. A synonymous alteration, TCG to TCC at codon 219 in exon 4 of the LMX1B gene, was identified in a Korean family with NPS. Serine is translated from codon TCG or TCC. At this codon, this same mutation has been previously identified in familial NPS cases, resulting in no amino acid change [1].

Human NPS mutations are present predominantly in exon 2 and to a lesser extent in exons 3, 4, 5, and 6 (85%), and include single-base substitutions (missense, splice site, nonsense, or frameshift mutations) and deletions or insertions [9]. The other 15% of mutations presumably lie deep within introns or involve deletion of all or part of the gene. The presence of these latter mutations most likely leads to a severe reduction in the levels of mutant transcript compared to normal alleles, which would result in very little, if any, synthesis of abnormal proteins [10]. Recent reports show that synonymous substitutions are not pathogenic mutations, based on sequencing over 200 unrelated individuals [11]. In addition, this single allelic nucleotide, TC [G/C] in codon 219, has been reported to have a high frequency of heterozygosity (0.46) in the general population. Therefore, a pathogenic role for this silent mutation, TCG to TC [G/C] in the LMX1B gene, remains to be defined. A possible explanation of the observed phenomenon is that epigenetic silencing can be a mechanism of disease development in patients without genetic abnormality. In addition, the possibility of an alternation at the protein level cannot be excluded [12,13]. We could not, however, demonstrate any segregation of this synonymous mutation with the disease. In addition, we did not conduct functional analyses of mutant proteins detected in the patients to elucidate either the transcriptional or the DNA-binding activity of these mutant proteins. Therefore, care should be taken when interpreting the results of this study, as the possibility cannot be ruled out that the G-to-C change, which is silent, is a single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Although many studies continue to identify mutations in patients with NPS, no obvious correlation is found between the presence and severity of clinical features of NPS and the type or location of known LMX1B mutations. In the five patients with NPS discussed in this report, clinical manifestations among the affected members and the severity of their symptoms were variable. Additional genetic studies in large, clinically well characterized families with NPS are necessary to evaluate the possible influence of modifying alleles on phenotypic expression and variability.

In this report, we presented a patient with NPS, characterized by nail dystrophy, iliac horns, open-angle glaucoma, and nephropathy. DNA analysis of the patient showed a synonymous alteration of TCG to TCC in exon 4 of the LMX1B gene, with no alteration in amino acid sequence.

Notes

This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (HMP-00-GN-01-0002).

References

1. Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Molec Genet 1998;7:1091–1098PMID : 9618165.

2. Lubec B, Arbeiter K, Ulrich W, Frauscher G. Hereditary osteoonycho-renal dysplasia with excess urinary pyridinoline cross-links and abnormal kidney collagen cross-linking. Nephron 1995;70:255–259PMID : 7566313.

3. Koo BS, Kim SJ, Kim PK, Choi IJ, Oh KK, Park HW. Two cases of nail patella syndrome. Korean J Nephrol 1993;12:459–463.

4. Bongers EM, Huysmans FT, Levtchenko E, et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in nail-patella syndrome show that LMX1B mutation location is involved in the risk of developing nephropathy. Eur J Hum Genet 2005;13:935–946PMID : 15928687.

5. Han SY, Kang MK, Whang EA, et al. A case of nail-patella syndrome who presented with characteristic electron microscopic findings. Korean J Nephrol 2002;21:837–841.

6. Lichter PR, Richards JE, Downs CA, Stringham HM, Boehnke M, Farley FA. Cosegregation of open-angle glaucoma and the nail-patella syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124:506–515PMID : 9323941.

7. McIntosh I, Clough MV, Schaffer AA, et al. Fine mapping of the nail-patella syndrome locus at 9q34. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:133–142PMID : 8981956.

8. Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al. Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail-patella syndrome. Nat Genet 1998;19:47–50PMID : 9590287.

9. Clough MV, Hamlington JD, McIntosh I. Restricted distribution of loss-of-function mutations within the LMX1B genes of nail-patella syndrome patients. Hum Mutat 1999;14:459–465PMID : 10571942.

10. McIntosh I, Hamosh A, Dietz HC. Nonsense mutations and diminished mRNA levels. Nat Genet 1993;4:219. PMID : 8358428.

11. Hamlington JD, Jones C, McIntosh I. Twenty-two novel LMX1B mutations identified in nail patella syndrome (NPS) patients. Hum Mutat 2001;18:458. PMID : 11668639.

Figure 1

Simplified pedigree of a family with NPS. Circles indicate women, squares denote men, and black symbols represent the affected individuals; diagonal lines across symbols specify deceased indivisuals; the arrow indicates the proband.

Figure 2

Patient with nail-patella syndrome showing (A) a dystrophic nail with longitudinal ridging and (B) bilateral iliac horns (arrows).

Figure 3

Electron micrographs of renal biopsy (proband III-2) with nail-patella syndrome. (A) The glomerular basement membrane shows prominent segmental thickening with irregularly shaped electron-lucent areas (uranyl acetate-lead citrate, ×17,000). (B) Dark fibrillar collagen bundles are located within the electron-lucent areas of the glomerular basement membrane (phosphotungstic acid, ×30,000).

Figure 4

Automated sequence anlaysis of exon 4 from the LMX1b gene. (A) The panel showed the synonymous G-to-C alteration. In addition, it showed a G-to-C transition that result in no amino acid change (arrow). (B) The results founded in affected patients is not shown in unaffected family member. Green lines, adenosine residues (A); blue lines, cytosine (C); black lines, guanine (G); redlines, thymine (T).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print